EARLY OPTICAL INSTRUMENTS AND THE PERCEPTION OF MOTION

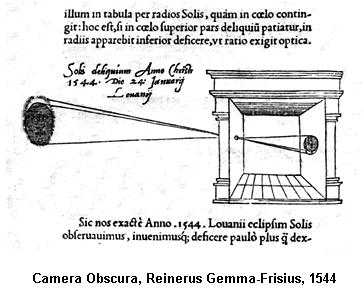

- The camera obscura:

A Renaissance optical tool used for causing images to appear through a pinhole in a dark room is the camera obscura'

- The description of the camera obscura

If the objects moved, the motion was reproduced on the wall. The early 18th century essayist Addison described the camera obscura for its image-making capacity; he also emphasised its capacity to record the motion of the objects placed opposite

Addison The Spectator N°414, Wednesday, June 25, 1712

The prettiest Landskip I ever saw, was one drawn on the Walls of a dark Room, which stood opposite on one side to a navigable River, and on the other to a Park. The Experiment is very common in Opticks. Here you might discover the Waves and Fluctuations of the Water in strong and proper Colours, with the Picture of a Ship entering at one end, and sailing by Degrees through the whole Piece. On another there appeared the Green Shadows of Trees, waving to and fro with the Wind, and Herds of Deer among them in Miniature, leaping about upon the Wall. I must confess, the Novelty of such a Sight may be one occasion of its Pleasantness to the Imagination, but certainly the chief Reason is its near Resemblance to Nature, as it does not only, like other Pictures, give the Colour and Figure, but the Motion of the Things it represents.

- Later versions of the camera obscura

They have remained as an entertainment to this day , where the visitors can watch the images of the passers-by walking in the street below.

- Optical tricks and the transformation of shapes

Scientists invented optical tools which could transform an image into another.

In the mid-17 th century, a rotating cylinder with pictures of several animals would reflect them in sequence in a mirror, giving the viewers the illusion that their heads successively changed into that of the various animals (by Athanasius Kircher). See the recent exhibition at the Hayward Gallery, London: Eyes, Lies and Illusions.